|

|

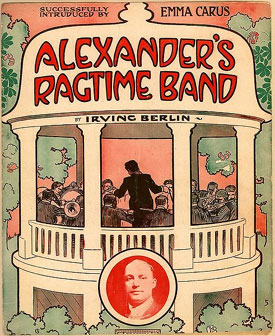

Ben & Brad - In the Media"Alexander's Ragtime Band" at One Hundred  Irving Berlin around the time of "Alexander's Ragtime Band"

Irving Berlin around the time of "Alexander's Ragtime Band"

March 18, 2011 will be the one hundredth anniversary of Irving Berlin's hit song "Alexander's Ragtime Band." The song's immediate and enduring popularity are now legendary. Berlin was a well-established songwriter by 1911, having had his first song published in 1907 and turning out many more – hits and misses – in the following years. Among the early hits were, "Dorando" (March 11, 1909), "Sadie Salome (Go Home)" (April 2, 1909), "My Wife's Gone to the Country (Hurrah! Hurrah!)" (June 18, 1909, one of his own favorites)1, "That Mesmerizing Mendelssohn Tune" (December 22, 1909), and "Call Me Up Some Rainy Afternoon" (April 23, 1910). A look at the history of this durable song and some perspective on why it stood out from Berlin's other early songs follows. The Creation of a Song Irving Berlin famously worked at night as he found it hard to sleep during what were usual hours for most people. So, it was overnight in March that he wrote "Alexander's Ragtime Band," submitting it for copyright on March 18, 1911 (presumably the day the composition was finished). Or did he? The song's original form and creation remain topics of debate. One version of the story, which Berlin himself supported, was that he wrote it as a piano solo first, perhaps as early as 1910. It does seem that in the summer or fall of 1910 he transcribed at least the basic tune, if nothing else. The March 18, 1911 copyright card states "words and music by Irving Berlin," so however long it took to create both those words and music, they were done by that date. A later version was submitted for copyright on September 6, 1911 as a piano solo. Alexander Woollcott, Berlin's friend and first biographer, gave this account of the song's creation in his 1925 The Story of Irving Berlin. "'Alexander' differed, too, in having been fashioned as an instrumental melody with no words to guide it. As such it gathered dust on the shelf, wordless and ignored, until one day when he himself needed a new song in a hurry. He had just been elected to the Friars' Club and the first Friars' Frolic was destined for production at the New Amsterdam. He wanted something new to justify his appearance on the bill and so he patched together some words that would serve to carry this neglected tune of which he was secretly fond. In his haste, he took the cue for the lyric from an already published and quite unsuccessful song of his called 'Alexander and His Clarinet.' For he alone among the writers of the world seems to have no unpleasant associations with the name Alexander. Usually when you see that name affixed to a character in a novel, you must be prepared to discover that character foreclosing a mortgage on some lorn widow, or, at the very least, assaulting an innocent country lass down some shady lane."2 Earlier than the account given to Woollcott, Berlin alluded to some indifference to the song in the first Music Box Revue (1921) in the "Interview" where he was asked about it by eight female reporters.

Whether Berlin himself really did hate it or was secretly fond of it, Edward Jablonski posited that apparently it caused some concern in the Ted Snyder Publishing offices. The song ran "beyond the conventional 32 bars; [and] it was too rangey ('an octave and four' which made it difficult to sing)."4 Whether this concern was voiced before or after Berlin wrote the lyric is unclear; if he was reluctant to add words to the tune, his employer's opinion may have contributed to that reluctance. The physical evidence, such as the copyright card, does not support the piano solo version of the story. As mentioned earlier, he did later publish a piano solo version, called "Alexander's Ragtime Band – March and Two-Step," on September 6, 1911. This version appears to have been created to capitalize on the song's success, as opposed to being a belated publication of the original piano rag. Charles Hamm, in his article Alexander and His Band gives a strong argument for the piano rag version being apocryphal, including the fact that up to this time Berlin had never published a solo piano piece and that no such unpublished pieces have come to light.5 Berlin himself added to the confusion not only in his reference in the 1921 Music Box Revue, but also in a 1920 article in which he told of the song's Friars Club premiere (see below) with the comment, "I hastily wrote a lyric, silly in the matter of common sense, that fitted the instrumental manuscript lying in my desk, and sang it, 'Alexander's Ragtime Band,' at the club performance."6 A piano arrangement of "Alexander's Ragtime Band" was published in All-American Ragtime, Volume 4, a collection of piano pieces from the early 20th century, with no attribution other than "by Irving Berlin."7 This is not the same piece published by Berlin in September of 1911, and so far its origins have not been ascertained, though it does fit the picture of a piano version predating the song – if, in fact, it predates the song.8 The Song's Genre: Is It Ragtime?  Original sheet music, with misspelling "intruduced"

Original sheet music, with misspelling "intruduced"

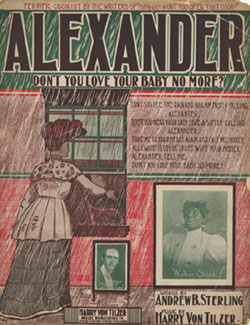

That Berlin wrote a song about a band is hardly unusual in his output. Berlin wrote probably more songs about music in one way or another than any other popular songwriter. "Alexander" was by no means the first, having been preceded by such songs as "Sadie Salome (Go Home)" (April 2, 1909, about a cooch dancer), "Wild Cherries (Rag)" (August 12, 1909), "Stop That Rag (Keep On Playing, Honey)" (November 24, 1909), "Yiddle on Your Fiddle Play Some Ragtime" (November 30, 1909), "That Mesmerizing Mendelssohn Tune" (December 22, 1909), "Grizzly Bear" (April 19, 1910), "Alexander and His Clarinet" (May 19, 1910), "Oh, That Beautiful Rag" (July 7, 1910), "Piano Man" (October 5, 1910), and "That Kazzatsky Dance" (December 19, 1910) to name only some. Over the years his songs about music covered a wide range of subjects, including dances, dancers, dancing, instrumentalists, opera, and songs about songs. As the definitions of ragtime narrowed over the years, particularly following the renewal of interest in the music of Scott Joplin and his contemporaries, it became fashionable to point out – usually in strongly emphatic terms – that "Alexander's Ragtime Band" is not a rag. If one does consider the form for instrumental, especially piano, works as followed by Joplin and his many contemporary composers of piano rags as the standard, then the Berlin song does not qualify. As with so much surrounding "Alexander's Ragtime Band," it deserves further analysis. Piano rags and the songs called ragtime feature a rhythmic pattern of an accented weak beat, along with a regular short-long-short pattern of notes. Both had their roots in the cakewalk popular in the late nineteenth century. Generally, in the early twentieth century the term "ragtime" covered a wide range of "songs and pieces for instrumental ensembles, particularly marching or concert bands."9 One simple definition of "ragtime" was music that "has to do with the Negro."10 Music having "to do with the Negro" is another aspect of how "Alexander's Ragtime Band" was perceived by contemporaries. One genre of popular song in the early twentieth century was the "coon song," a term fortunately now lost.11 Songs dealing with various ethnicities – in particular Irish, Asians, Jews, Negroes, all usually in a derogatory fashion – were common currency in that era. "Alexander's Ragtime Band" has been considered by many to be a coon song, and arguments have been made that 1911 audiences perceived it as such.  "Alexander, Don't You Love Your Baby No More?"

"Alexander, Don't You Love Your Baby No More?"

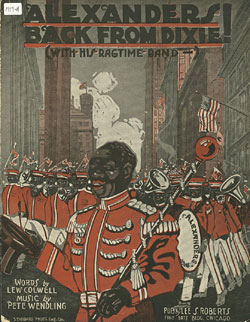

Lawrence Bergreen gives a short history of the name "Alexander" as an ethnic marker (as opposed to the villainous connection made by Woollcott). "The idea behind the song derived from a long line of 'Alexander' songs instigated by Harry Von Tilzer in 1902, and he, in turn, had borrowed the Alexander character from a popular turn-of-the-century minstrel act, Montgomery and Stone. The two white entertainers, who performed in blackface, were sure to get a laugh whenever they started calling each other 'Alexander,' a name their audiences considered too grand for a black man."12 Charles Hamm lists "Alexander" as a coon song in his forward to Irving Berlin: Early Songs, 1907-1914 (1994), then argues against it in Alexander and His Band (1996). "...[T]he protagonist's excited invitation to his 'honey' to come along and listen to the 'best band in the land' is nothing of the sort. The gesture of the piece, a first-person exhortation to anyone and everyone within earshot to come and listen to a band, has no precedent in earlier 'coon' songs or any other songs of the Tin Pan Alley era. . ."13 By Bergreen's definition, audiences in 1911 automatically understood that "Alexander's Ragtime Band" was a coon song by simple virtue of the name Alexander in the title. Berlin had already used that name as a racial marker, in keeping with that cultural norm, when he wrote "Alexander and His Clarinet" in May, 1910, a song clearly about a black protagonist. As Bergreen explains it, "When Berlin and Snyder sat down to write a raunchy 'coon' number entitled 'Alexander and His Clarinet,' they were describing, with the help of numerous double entendres, yet another highly sexed 'coon.'"14 Adding to the confusion, though, is the fact that the sheet music cover of "Alexander," as noted by Hamm in Irving Berlin: Songs from the Melting Pot, shows a band which, on close examination, appears to be racially integrated and the skin color of the "Alexander" leading the band is ambiguous. This ambiguity is perhaps not surprising when considering that one of the remarkable aspects of Berlin's early songwriting is that his ethnic songs tended to move away from the derogatory quality commonly found in such songs. Along with "Alexander," Berlin songs such as "When the Midnight Choo-Choo Leaves for Alabam'" were originally written and performed as coon songs, yet as seen in later performances (e.g., in the films Alexander's Ragtime Band and Easter Parade) such songs would and still can be performed void of their ethnic markers and not suffer for the loss. Musically, "Alexander's Ragtime Band" is a march, a quick two-step with syncopations. Again, this does not prevent it from being ragtime as understood at the time, though many modern critics have used this as the argument against it being ragtime. By the time he wrote "Alexander," Berlin had used the word "rag" or "ragtime" in seven song titles (not to mention others with allusions to ragtime or, in the case of "Grizzly Bear," setting words to an extant rag by another composer). The songs are "Stop That Rag (Keep on Playing, Honey)" (November 24, 1909), "Yiddle, On Your Fiddle, Play Some Ragtime" (November 30, 1909, in Jewish "dialect"), "Draggy Rag" (April 13, 1910), "Sweet Marie, Make-a Rag-a-time Dance Wid Me" (January 18, 1910, with an Italian "dialect"), "That Opera Rag" (April 28, 1910, about an "opera darkie"15), "Oh, That Beautiful Rag" (July 7, 1910), and "That Dying Rag" (February 18, 1911). From code words in their titles two of the songs are easily identifiable as ethnic songs, one Italian, one Jewish. A third, as revealed in the lyric rather than the title, has a Negro protagonist (and a fourth song might have been assumed to have a black protagonist). Given this sampling it appears that Berlin did not associate "ragtime" strictly with blacks. Keep in mind that the song never says that it, itself, is ragtime, but rather it is a song about a band which plays ragtime. Charles Hamm sums up the question of its legitimacy as ragtime thus: In the end, arguments over whether or not "Alexander" draws on specific elements of ragtime or looks like a piece of ragtime on the page, are pointless. It was a piece of ragtime music, and as such it helped define the genre for its audiences.16 Early Years According to Jablonski's account, Berlin submitted "Alexander" to Jesse L. Lasky for a new theatre, The Follies Bergère, with a lyric which was not used.17 The song was whistled by Otis Harlin (or Harlan), whose rendition made no impression, and also suffered from a poor effort from the orchestra. When invited to appear in the 1911 Friars' Frolics on May 28, 1911, Berlin "submitted the somewhat tattered and pretty much unsung 'Alexander's Ragtime Band.' [George M.] Cohan, no mean judge of a song himself, was the first to respond to it. On hearing its composer sing it, he exclaimed, 'Irv, that's the song you'll do!' So it was Irving Berlin who introduced 'Alexander's Ragtime Band' at the New Amsterdam Theater on May 28, 1911. He was joined by famed lyricist Harry Williams ('In the Shade of the Old Apple Tree') in a double. This introduction of the song was not devoid of energy for, as recalled by the composer, 'we sang, did a little dance – and went off with a cartwheel.' This vigorous rendition lit the flame that was to sweep the nation, for the Friars' Frolics went on a cross-country tour."18  "Alexander's Back from Dixie!"

"Alexander's Back from Dixie!"

Once it caught on the song appeared with regularity throughout 1911. It was interpolated into The Merry Whirl, which opened June 12 at the Columbia Theatre, sung by James C. Morton and Frank F. Moore to great acclaim.20 Apparently the management felt audiences simply expected to hear "Alexander" at the Columbia as the very next show there, Trocaderos, again featured the song. At the Casino Theatre in Brooklyn, a show called The Whirl of Mirth tried cashing in on the song's success in The Merry Whirl by featuring it. Vaudeville performers quickly took it up, including Berlin again, in a solo vaudeville turn in September. The song's ubiquitous presence led Variety, on September 9, 1911, to call it the "musical sensation of the decade". All this in less than a year. Its presence in vaudeville led one theatre manager in Cleveland to find himself with five acts performing the song. He told four to "cut that band song out."21 Berlin himself took advantage of the song's popularity by reusing its ideas or referencing it in later songs. The first instance came quickly, with a musical quote in "Whistling Rag," published on March 31, 1911. He later quoted extensively – musically and with allusions in the lyric – in "Alexander's Bagpipe Band," which came out eleven months later on February 10, 1912. The theme, or general feel, of "Alexander" found its way into two other 1912 songs, "Lead Me to That Beautiful Band" (April 18) and "A Little Bit of Everything" (October 18), and later "Follow the Crowd" (January 30, 1914). These songs have syncopation and the "raggy" feel that came to be synonymous with ragtime, and were features of "Alexander." "Lead Me to That Beautiful Band" draws in the lyric on allusions similar to the earlier song: ...lend an ear to the finest music in the land The chorus, in turn, tells of the individual instruments in the band, expanding on the earlier idea of "they can play a bugle call like you never heard before." "A Little Bit of Everything," while not directly referencing band music, has the exhortations of "come, honey, come" and "you better hurry up and come with me" that are echoes of "come on and hear!" Finally, "Follow the Crowd" plays on the idea of "the bestest band what am" with "...a jewel of an orchestra/ Best of the rest in America." It also features the now-familiar exhortation, this time as "Come, my honey, come."22 "Come on and hear" makes a reappearance in "When Johnson's Quartette Harmonize" (June 11, 1912) in the opening of the chorus, "come on and hear that harmony sweet, come and have a musical treat." Nothing in the text identifies this as an ethnic song, though Johnson Jones ("father of sweet harmony"), the leader of the quartet, is from Tennessee, which may have been enough of marker to consider it to be about black singers.  "When Alexander Takes His Ragtime

"When Alexander Takes His RagtimeBand to France" Other specific quotations include a fascinating "medley" of Berlin's hits published November 11, 1913 called "They've Got Me Doing It Now," which used "Everybody's Doing It Now" as its basis and expanded on the theme, bringing in allusions to a number of Berlin songs including "When the Midnight Choo-Choo Leaves for Alabam'," "That Mysterious Rag," "Ragtime Violin," and, of course, "Alexander's Ragtime Band." He somewhat repeated this idea in the first Music Box Revue of 1921, in the "Interview" as noted above. A reference to "Alexander" as a bandleader appears in his 1918 song, "Send a Lot of Jazz Bands Over There" from Yip! Yip! Yaphank! in which he exhorts President Woodrow Wilson to "send a troupe of Alexanders with their jazz bands off to Flanders."23 A trio of songwriters under contract to Berlin's publishing house, Waterson, Berlin & Snyder, joined Berlin in writing about Alexander and his band (presumably with his blessing, as publisher). Alfred Bryan, Cliff Hess, and Edgar Leslie wrote "When Alexander Takes His Ragtime Band to France" in 1918, quoting both the words and music for "come on along" from Berlin's song, making it clear just which band would be going "over there." In 1920 Max C. Freedman and Harry D. Squires published "When Alexander Blues the Blues," which musically alludes to the "oh ma honey" phrase and in the lyric mentions this piano playing Alexander working his magic on "Swanee River," just like Berlin's Alexander ("when he starts to blue that old Swanee River, too"). Berlin also wrote two parodies of "Alexander's Ragtime Band," adding new lyrics to the tune. The first, written April 10, 1972, was prompted by the possibility that the song's copyright would expire (the laws were rewritten, but Berlin still did manage to outlive the copyright). Berlin clearly was opposed to the law as it stood, but took wry consolation that he was "in the club with Stephen Foster's 'Swanee River.'" The other comes from the very end of his life, dated June 23, 1987, called "Mister Alexander Coh'n." Cohen was a Broadway producer who was planning a show (eventually unproduced) called Broadway's Best which would feature songs by Berlin, the Gershwins, Kern, Porter, Rodgers, and others (according to Berlin's lyric). Berlin again makes reference to "Swanee River" ("he'd close the show with Stephen Foster's 'Swanee River'").24 An unusual story around the early years of "Alexander" concerns, of all people, the Russian mystic Grigori Rasputin. The life and death of Rasputin are still mysterious, with the facts of his death uncertain and likely to remain so. Ian Whitcomb, in his quirky study Irving Berlin and Ragtime America (1988), presents a fascinating version of Rasputin's death, involving "Alexander's Ragtime Band." A new recording of the latest American ragtime hit, "Alexander's Ragtime Band," apparently was a lure used to get Rasputin to the house where we was to be murdered. It is hard to know if this story is true, but it casts an interesting light on the power of Berlin's music, and a fascinating connection to the country where he was born. Recordings, Film, and Stage "Alexander's Ragtime Band" received its first recordings in May and June, 1911, though the discs were not released until September. In both cases the performers were Arthur Collins and Byron G. Harlan, who made six total recordings (for six different companies), all of which were released in September. In November came three recordings by Billy Murray, which are now considered the classics of the early recorded versions. Arrangements for both band and "orchestra" followed, along with a banjo arrangement by Fred Van Epps released in May 1912 and re-recorded for release in September 1913.  "Alexander's Band is Back in Dixieland"

"Alexander's Band is Back in Dixieland"

Subsequent recordings, by no means a complete list, include Al Jolson (solo), Jolson with Bing Crosby, Crosby with Connee Boswell, Boswell with her sisters (the Boswell Sisters), the Andrews Sisters, Julie Andrews, No‘l Coward, Alice Faye, the Benny Goodman Orchestra, Ted Lewis, Johnny Mercer, Ethel Merman (on the now infamous Disco album), Kid Ory's Creole Band, Johnny Ray, Joe Venuti, Max Morath, and the classic Bessie Smith version.25 For all its popularity, "Alexander's Ragtime Band" has appeared in only three musical films, two of which are Irving Berlin "catalogue" movies. The first was Alexander's Ragtime Band, released in 1938 in conjunction with Berlin's fiftieth birthday, in which the song bookends the film, befitting its status as the title number. The original intent was for the film to be Berlin's life story. Berlin was uncomfortable being impersonated in any kind of dramatization and refused permission.26 He was willing to let his catalogue be used and a script was devised, using many of his early songs, with "Alexander" as an exemplar of "swing songs" (as the "Alexander" character calls it late in the film). Berlin did write some new songs, including "My Walking Stick," "Marching Along With Time" (cut, but used as an instrumental under the opening credits), and the lovely ballad "Now It Can Be Told." The film stars Alice Faye and Tyrone Power as star-crossed lovers brought together by the title song. In secondary roles are Don Ameche (rounding out the love triangle), Ethel Merman, and Jack Haley. Power is a classical violinist named Roger who moonlights leading a jazz ensemble to earn money. He stumbles on a new song, "Alexander's Ragtime Band," which Faye has just acquired and hopes to use in her act. The band is confounded by the "new music" in a scene perhaps reminiscent of the Follies Bergère incident where the "orchestra flailed away at Berlin's instrumental."27 Faye accuses Power of stealing it, but he talks her into working with him, as she clearly understands how to put over this new style of song. Renamed Alexander through his association with the song, Power goes from strength to strength in show business with his group, now called Alexander's Ragtime Band, but loses Faye to Ameche (though they later divorce and Faye disappears from both men's lives). Ultimately "the first and best of all swing songs" (as Power calls it in the film's final scene) brings Faye back to him, when swing goes legit and Alexander's Ragtime Band appears at Carnegie Hall in New York. After the enormous success of the American run of This Is The Army, a film of that title was made. Hollywood changed the show from a revue to a one with a fairly standard Hollywood plot, but retained the Berlin score, including Berlin himself singing "Oh How I Hate to Get Up in the Morning." Just before Berlin's appearance some of the World War I veterans repeat a drill routine from Yip! Yip! Yaphank! (Berlin's World War I Army show) to "Alexander's Ragtime Band." In 1954 Ethel Merman again was connected with "Alexander's Ragtime Band" on film, this time singing it in There's No Business Like Show Business, another collection of older Berlin songs, rounded out with a couple of new ones. Merman had been denied the role of Annie Oakley in the film version of Annie Get Your Gun, so There's No Business Like Show Business can be seen as the opportunity to let her sing the title song – now a Merman signature tune – on screen. No biographies of either Merman or Berlin state the situation as such, but it seems obvious that the film was conceived, in part, to allow her a permanent cinematic record of the song. Merman is the mother of the vaudeville family the "Five Donahues" (or rather, the "Two Donahues," then Three, Four, and Five), with dad Dan Dailey and children Johnny Ray, Donald O'Connor, and Mitzi Gaynor. Marilyn Monroe rounds out the cast as O'Connor's love interest (and rival for some Merman songs). While not the title song, as it was in the earlier film, "Alexander's Ragtime Band" serves as a bookend to the movie. It appears early in one of the film's largest production numbers and then as the finale when the cast is reunited. The production number is in six sections opening with the entire Donahue family singing. The sequence then takes a series of bizarre turns. It segues to Dailey and Merman doing what appears to be a Bavarian version, complete with lederhosen and faux German with a bit of a Swiss bell ringing act added to confuse the ethnic flavor (though it is mitigated somewhat in that it does allow Merman to indulge her natural comic sense). This is followed by O'Connor in kilts in a Scottish reel (reminiscent of Berlin's own "Alexander's Bagpipe Band"), then Gaynor in a French oo-la-la can-can version, culminating in the non-dancing Johnny Ray at his piano giving a solo rendition in his overwrought style (a low point in the production and the film). Whatever the problems of the "Alexander" production number, the overall film is entertaining, and a rare chance for Merman to display her star power onscreen. "Alexander" can be said to make a fourth appearance in a Berlin film. During the credits for the Astaire/Rogers Top Hat the background music switches from the new score to a snippet of "Alexander" when Berlin's name appears. The stage history of "Alexander's Ragtime Band" after the vaudeville appearances mentioned earlier is brief, but fascinating. An early appearance was in a Weber & Fields show, Hokey-Pokey which ran at the Broadway Theater from February 18, 1912 through May 11, 1912. "Alexander" was the Eleven O'Clock number, giving it pride of place.28 In Norton's Anthology of American Musical Theater, "Alexander" is listed as having music and lyrics by Irving Berlin, E. Ray Goetz, and A. Baldwin Sloane, suggesting that Berlin allowed extra lyrics to be written to suit the shtick of Weber & Fields; given their style presumably it was something in Yiddish dialect.29 In 1914 Berlin used "Alexander" for underscoring in one scene from his first Broadway score, Watch Your Step. Dancer Katherine Dunham was the director and choreographer for Bal Negre ("A Native Music and Dance Revue in Three Acts and Six Scenes") which she created for her own company. The show toured the U.S. for nine months before opening at the Belasco Theater on November 7, 1946 and closing shortly thereafter on December 22, 1946. "Alexander" was part of the "Ragtime Medley" along with non-Berlin songs "Chong," "Under the Bamboo Tree," "Ragtime Cowboy," and "Oh, You Beautiful Doll," sung by Rosalie King and the Sans-Souci Singers. The dances featured were a waltz, fox trot, tango, maxixe, Ballin' the Jack, and the Turkey Trot danced by Lucille Ellis, Lenwood Morris, and the ensemble. Michael Feinstein (1988) and Mandy Patinkin (1989) both presented concerts at Broadway theatres in which they featured "Alexander" – testimony to the song's continued importance to singers dedicated to the Great American Songbook. Recent History Even with changes in music and popular entertainment, "Alexander's Ragtime Band" remains an iconic American song. Recordings now are highly infrequent, especially as the recording industry changes, but continued interest in singers such as Al Jolson, Bing Crosby and Ethel Merman, along with cult favorites such as Connee Boswell and Bessie Smith keep their recordings of the song in circulation. Renewed interest in the stars of the two Berlin films featuring "Alexander," particularly Marilyn Monroe, Merman, Tyrone Power, and Alice Faye, insures the continued presence of those films on DVD. Few now remember Emma Carus or Billy Murray, the Friars' Club, or (unfortunately) even George M. Cohan; not many born since There's No Business Like Show Business probably could identify the composer of "Alexander's Ragtime Band." Nonetheless, the song itself remains as fresh as it did in 1911 when it took the nation, and even the world, by storm. Alexander's Ragtime Band Verse One: Oh ma honey, oh ma honey, Chorus: Come on and hear, come on and hear, Verse Two: Oh ma honey, oh ma honey, Some commentators consider "Oh, That Beautiful Rag" to be a precursor to "Alexander's Ragtime Band." The music is by Ted Snyder, with whom Berlin wrote a number of early songs, and bears no resemblance to "Alexander" other than some raggy rhythms. It is not as interesting as the music for "Alexander" which may explain its lack of continued popularity, though Berlin himself did sing it with Snyder in the show Up and Down Broadway (1910). The lyrics, by Berlin, can be considered a kind of dry run for the later song. Oh, That Beautiful Rag (published July 9, 1910) Verse One: Honey, that leader man Chorus: Oh! Oh! Oh! Oh! Verse Two: What does my honey want? Bibliography Bergreen, Lawrence, As Thousands Cheer: The Life of Irving Berlin. New York: Viking, 1990. Crawford, Richard, American's Musical Life. New York: W.W. Norton, 2001. Furia, Philip, Irving Berlin: A Life in Song. New York: Schirmer Books, 1998. Hamm, Charles, Irving Berlin: Early Songs, 1907-1914 (3 volumes) (Volume 2 of the series Music in the United States. Madison, WI: A-R Editions, 1994. Hamm, Charles, "Alexander and His Band," American Music, Spring 1996 (largely reprinted in Irving Berlin: Songs from the Melting Pot). Hamm, Charles, Irving Berlin: Songs From the Melting Pot: The Formative Years, 1907-1914. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. Jablonski, Edward, "Alexander and Irving," from Listen – A Musical Monthly, October-November, 1963. Kimball, Robert and Linda Emmet, eds., The Complete Lyrics of Irving Berlin, New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2001. Norton, Richard C., A Chronology of American Musical Theatre, New York: Oxford University Press, 2002. O'Malley, Frank Ward, "Irving Berlin Gives Nine Rules for Writing Popular Songs," American Magazine, October 1920. Wolf, Rennold, "The Boy Who Revived Ragtime," Green Book Magazine, August 1913. Woollcott, Alexander, The Story of Irving Berlin, New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1925. Notes 1 Berlin often cited this song in early articles about his songwriting techniques. 2 Alexander Woollcott, The Story of Irving Berlin (G.P. Putnam's Sons, New York, 1925), pg. 87-88. 3 "The Interview" has been recorded by this author (as Irving Berlin) with Bradford Conner and members of the American Classics ensemble on the CD Everybody Step, a collection of songs from Berlin's Music Box Revues (Oakton Recordings, ORCD 0008). 4 Edward Jablonski, Alexander and Irving," Listen – A Musical Monthly, October-November, 1963. 5 Charles Hamm, "Alexander and His Band," American Music, Spring 1996, pg. 78. 6 Frank Ward O'Malley, "Irving Berlin Gives Nine Rules for Writing Popular Songs," American Magazine, October 1920. 7 Published by Creative Concepts Publishing (Ventura, CA, 1989). It does say "©1911 by Irving Berlin," as if it were a reprint but gives no other information. 8 For more information on the early history of the song and Irving Berlin, see Edward Jablonski, "Alexander and Irving," Listen – A Musical Monthly, October-November, 1963 and Charles Hamm, "Alexander and His Band," American Music, Spring 1996 at 65 (reprinted, with revisions, in Irving Berlin: Songs from the Melting Pot: The Formative Years, 1907-1914, New YOrk: Oxford University Press, 1997). Hamm, in particular, discusses some of the controversies around the authorship of the song, gives a full account of its early history, and discusses the song's form and structure. The entry on "Alexander's Ragtime Band" in The Complete Lyrics of Irving Berlin (edited by Robert Kimball and Linda Emmet, Alfred Knopf, New York, 2001) has two extensive quotes by Berlin on the creation of the song. 9 Hamm, Irving Berlin: Songs from the Melting Pot: The Formative Years, 1907-1914, pg. 106. 10 E.M. Wickes, Writing the Popular Song, Home Correspondence School, Springfield, MA, 1916, pg. 33, as quoted in Hamm, Irving Berlin: Songs from the Melting Pot, pg. 104. 11 "Coon" was, and sometimes still is, a pejorative slang term for Negro. Such terms were prevalent in the early twentieth century and their widespread use often rendered them meaningless to their users; it simply was the term used. This is not to excuse that behavior, but rather to give it a context within its time. 12 Lawrence Bergreen, As Thousands Cheer: The Life of Irving Berlin (Viking, New York, 1990), 55-56. 13 Hamm, Alexander and His Band, 65-66. 14 Bergreen, 55-56. 15 Another unfortunate racial term that has lost currency. It was commonly used in the early twentieth century and Berlin was no exception, using it in his early songs and as late as 1942 in "Abraham" in the film Holiday Inn. When an African-American journal complained of its use in the song, Berlin pulled the sheet music and reissued it with the word changed to "Negro." 16 Hamm, Irving Berlin: Songs from the Melting Pot, pg. 106. 17 Whether this was the final lyric or a different (presumably lost) one is not made clear. 18 Edward Jablonski, "Alexander and Irving," Listen – A Musical Monthly, October-November, 1963. 19 Quoted in Hamm, Alexander and His Band, pg. 82. 20 Richard C. Norton, A Chronology of American Musical Theatre, Oxford University Press, 2002, pg, 936 notes in the listing for the The Merry Whirl that it was "previously and subsequently produced in New York under a vaudeville contract, performed twice daily." Apparently Trocaderos was also a vaudeville show as it does not appear in Norton's anthology. The Casino (also known as the DeKalb) Theater in Brooklyn was a "continuous vaudeville" house. 21 Hamm, Irving Berlin: Songs from the Melting Pot, pg. 130. 22 Berlin, especially in his earlier years, recycled and reused ideas in his songs, so his allusions to Alexander in later songs was not unusual for him. 23 In the early days of jazz and ragtime, the two terms were used interchangeably, so Berlin's allusion to Alexander and jazz, rather than ragtime, would not have been confusing. 24 Both parodies are reprinted in full in The Complete Lyrics of Irving Berlin. 25 More recently, this writer with pianist Bradford Conner performed it (along with the spurious piano solo) on their CD Come On And Hear! (Oakton Recordings, ORCD0001). 26 He never changed his feelings on this, to the point of refusing permission for a BBC television dramatization of his life as late as 1958. 27 Bergreen, 61. 28 Usually the song before the finale ultimo, and a star turn. The term comes from the fact that in that era of Broadway, with an 8:30 curtain time, the song was sung around 11:00. In vaudeville this was the prized spot on the billing, as audiences would leave early, skipping the finale. 29 Joe Weber and Lew Fields were one of the most popular vaudeville acts of the time, famous for their Yiddish dialect routines in particular. They later became producers. Fields was the father of lyricist Dorothy Fields and her show-writing brothers Herbert and Joseph. |